I ricercatori dell’Università di Turku in Finlandia hanno scoperto che l’asse di rotazione di a[{” attribute=””>black hole in a binary system is tilted more than 40 degrees relative to the axis of stellar orbit. The finding challenges current theoretical models of black hole formation.

The observation by the researchers from Tuorla Observatory in Finland is the first reliable measurement that shows a large difference between the axis of rotation of a black hole and the axis of a binary system orbit. The difference between the axes measured by the researchers in a binary star system called MAXI J1820+070 was more than 40 degrees.

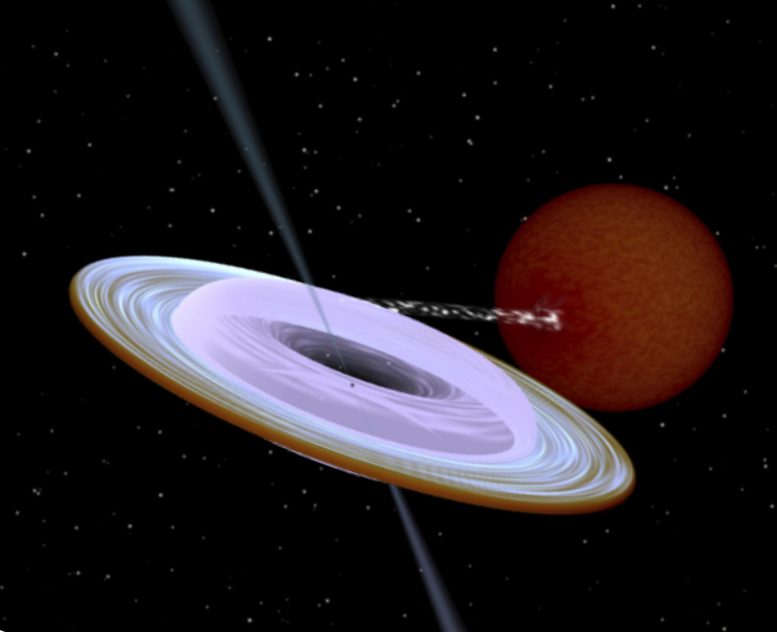

Artist impression of the X-ray binary system MAXI J1820+070 containing a black hole (small black dot at the center of the gaseous disk) and a companion star. A narrow jet is directed along the black hole spin axis, which is strongly misaligned from the rotation axis of the orbit. Image produced with Binsim. Credit: R. Hynes

Often for the space systems with smaller objects orbiting around the central massive body, the own rotation axis of this body is to a high degree aligned with the rotation axis of its satellites. This is true also for our solar system: the planets orbit around the Sun in a plane, which roughly coincides with the equatorial plane of the Sun. The inclination of the Sun rotation axis with respect to orbital axis of the Earth is only seven degrees.

“The expectation of alignment, to a large degree, does not hold for the bizarre objects such as black hole X-ray binaries. The black holes in these systems were formed as a result of a cosmic cataclysm – the collapse of a massive star. Now we see the black hole dragging matter from the nearby, lighter companion star orbiting around it. We see bright optical and X-ray radiation as the last sigh of the infalling material, and also radio emission from the relativistic jets expelled from the system,” says Juri Poutanen, Professor of Astronomy at the University of Turku and the lead author of the publication.

Rappresentazione artistica del sistema a raggi X binario MAXI J1820 + 070, che contiene un buco nero (un piccolo punto nero al centro del disco gassoso) e una stella compagna. Un raggio stretto è diretto lungo l’asse di rotazione del buco nero, che è fortemente deviato dall’asse di rotazione dell’orbita. La foto è stata scattata con un gioco da ragazzi. Credito: R. Hynes

Tracciando questi getti, i ricercatori sono stati in grado di determinare con precisione la direzione dell’asse di rotazione del buco nero. Successivamente, quando la quantità di gas che cadeva dalla stella compagna nel buco nero iniziò a diminuire, la temperatura del sistema si raffreddò e gran parte della luce entrò nel sistema dalla stella compagna. In questo modo, i ricercatori sono stati in grado di misurare la pendenza dell’orbita utilizzando tecniche spettroscopiche, e questo ha coinciso grosso modo con la pendenza della balistica.

“Per determinare l’orientamento 3D dell’orbita, devi anche conoscere l’angolo di posizione del sistema nel cielo, il che significa come il sistema ruota rispetto alla direzione nord nel cielo. Questo è stato misurato utilizzando tecniche di polarimetria”, dice Guri Potanin.

I risultati pubblicati su Science forniscono prospettive interessanti per gli studi sulla formazione di buchi neri e sull’evoluzione di questi sistemi, dal momento che uno squilibrio così estremo è difficile da ottenere in molti scenari di formazione di buchi neri e di evoluzione binaria.

La differenza di oltre 40 gradi tra l’asse orbitale e la rotazione del buco nero era del tutto inaspettata. Gli scienziati hanno spesso ipotizzato che questa differenza fosse molto piccola quando hanno modellato il comportamento della materia in uno spaziotempo curvo attorno a un buco nero. I modelli esistenti sono già complessi e ora le nuove scoperte ci stanno costringendo ad aggiungere una nuova dimensione ad esso”, afferma Potanin.

Riferimento: “Disallineamento della rotazione del buco nero orbita-orbita nel binario a raggi X MAXI J1820+070” di Guri Potanin, Alexandra Veledina, Andrei in Berdyugina, Svetlana in Berdyugina, Helen Germack, Peter J. Vadim Kravtsov Filippo Pirola, Manisha Shresta, Manuel A. Perez-Torres, Serge S. Tsygankov, 24 febbraio 2022 Disponibile qui. lo so†

DOI: 10.1126 / science.abl4679

La scoperta principale è stata effettuata utilizzando un polarimetro DIPol-UF costruito internamente e installato nel Northern Optical Telescope, di proprietà congiunta dell’Università di Turku con Università di Aarhus in Danimarca.